[Note that this post was written in March 2022, shortly after the full-scale invasion of the Ukraine by the Russian Federation.]

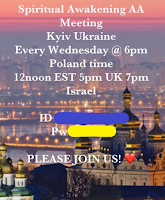

An A.A. friend sent me a very well-done flyer for an online A.A. meeting in Kyiv, Ukraine. It's shown to the left, but I've removed the Meeting ID and Passcode; I don't want to make it that easy to attend. When I first saw it, I thought, "I only wish that we could do something similar for all the Russian alcoholics, who must also be terribly distressed at this time" (especially those in the Russian military).

This flyer was immediately followed by a less well-done message,

shown below, purporting to be from "Ukrainian AA Service Center

and the Ukrainian AA Service Board" to "the AA World Community." I was

skeptical. This looked so much like a myth that I expected to

find it debunked at Snopes

("the internet’s definitive fact-checking

resource"). I did not. But I did find an article titled, "UKRAINE: New Crisis, Grimly Familiar Disinformation Trends", which said, in part,

It is a grim measure of the frequency of crisis events in recent years, and the ubiquity of online disinformation, that when a major story breaks — a terrorist attack, a mass shooting, or an act of war — the writers and editors at Snopes can typically predict what comes next. Recycled videos and photographs, stripped from their proper context, and the same old tropes, all designed to inflame or confuse, or even amuse, the reader.

This is followed by a "grim overview of the familiar disinformation trends and recurring memes… in the opening days of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine."

But, as I said, I only later looked on Snopes. First I searched the Internet. To my surprise, I immediately got a hit that looked very promising. It was on the aa.lviv.ua website and looked like this:

Since I don't know what I presumed was Ukrainian, and not having much patience, I immediately had the page automatically translated into English. It is indeed Ukrainian, and here's the English translation I got:

It was only later that I noticed that an English translation of the message follows the Ukrainian on the original, one click further down. I felt stupid and impatient for not looking.

Ultimately, I decided I'd check into the Kyiv online meeting and see if

there was some way I could be helpful. I tried to log in a few minutes before it was to start. Due to the meeting having reached

capacity, it was impossible to get in. It then occurred to me, If

I'm having this much trouble getting in, there are probably Ukrainians who are also unable to get in. It horrified me to think that I could have had a part in disrupting their meeting. If, by some miracle, I

had been able to get in, I sure hope I would have realized that the meeting was at capacity and left. But even if I had, my spot would have been filled by a non-Ukrainian.

I tried joining after the meeting was over. It was bedlam. It appeared that most people were unmuted and there were multiple conversations going on at the same time. I saw one man, who appeared to be that single Ukrainian member. He appeared to be quite stressed out. I also saw some A.A.friends of mine, which was disappointing. I only stayed a minute. The last thing they needed at that point was yet one more non-Ukrainian A.A. to join the fray.

Tonight, I learned from a reliable source that only one of the seven or eight regular Ukrainian group members was able to get into the meeting (presumably, the Zoom host). No doubt, many of the attendees had good intentions, although I'm also pretty sure some did not. Clearly, many also didn't think through the consequences of their actions.

And then, very late last night, My friend said that another friend of hers had found a Facebook post about the A.A. meeting in Kyiv earlier, shown at the left. It was so disheartening to read. Yes, many

non-Ukrainians—maybe hundreds of them

—got to feel good for a minute. Meanwhile, seven or eight locals never got to their meeting.

%20(1).jpg)